|

India Pale-Ale -IPA-

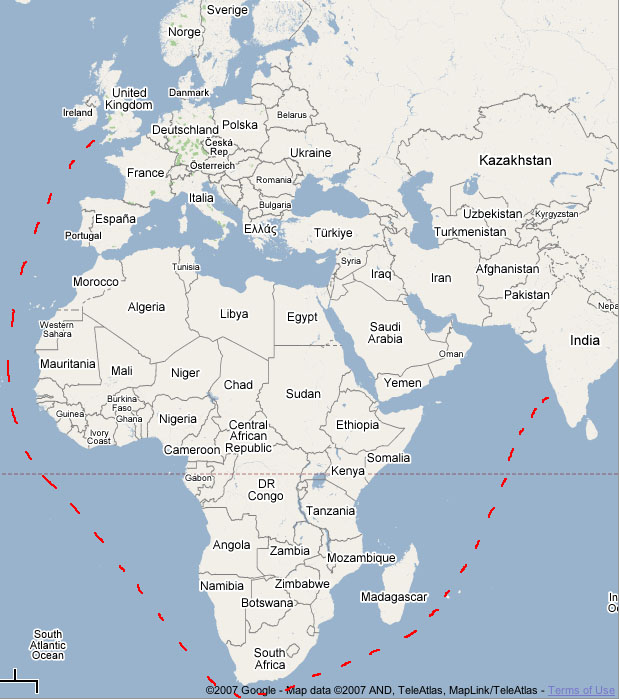

India Pale Ale - IPA -- the name stirs up images of tall ships and faraway places. A beer with such a name should have a bold and stirring character and the India Pale Ale (IPA) usually delivers. The bitterness, hop aroma, fruitiness, and high mineral content characteristic of IPA's offers an adventure in every pint. The IPA is an aggressive style that can be too bitter for the timid beer drinker and can prove itself much too strong for the amateur. In modern day, it seems that almost everyone knows that the IPA was originally a colonial beer formulated to handle the voyage from England to India. The higher hop and alcohol content helped to preserve it for the 6 months the beer would spend at sea before reaching the lips of thirsty, homesick British colonialists. But its important to know there is a lot more to the IPA than this. For beer lovers, the history of a style proves interesting and enlightening. This is particularly true for IPA lovers. More than having a place in the history of beer styles, IPA shaped the course of British brewing history. The problem facing the British during the 18th and 19th centuries was that beer did not keep well on long ocean voyages, especially voyages into hot climates. These hot environments often resulted in flat, sour beer. Voyages often lasted months, a long time for British sailors to go without a pint of beer. If such a situation were allowed, sailors would miss not only the cultural aspects of ale, but also the ready source of B vitamins that beer provided. However, plenty of beer was making it from England to India back in the late 1700s. In London, Porter was especially popular. Unlike today’s porter, it was strong—about 7.5 percent alcohol. Porters traveled especially well and successfully reached India prior to the introduction of IPA. But, a porter is not a Pale Ale... The British Admiralty was desperately searching for a way to transport beer to the far corners of the globe. It has been said that the Royal Society got involved as early as the mid-18th century and several ideas were under consideration. Finally, in 1772 Henry Pelham, Secretary to the Commissioner of Victualling, suggested that brewers simmer away most of the water from their wort. Once at sea the sailors could add water and let the beer "stand to acquire a proper spirit and briskness." Later that year, and early in 1773, Captain Cook and the officers of the Endeavour reported that the concentrate, combined with yeast and spruce, did quite well in cooler waters. However, reports started to come in about the concentrate's bad performance in warmer climates and inconsistent performance in cooler climates which led to the demise of on-board brewing from concentrate in the Royal Navy. Had the concentrate scheme been successful for on-board brewing, the Royal Admiralty's alliance with rum, which began in 1740, would probably have been less strong. Rum's high alcohol content was beneficial in that it conserved space, and it could be easily cut into grog with water, citrus juice, and sugar. But Beer was regarded as more temperate and healthful than hard liquor. However, the failure of the concentrate scheme forced them to settle for rum and British troops and colonists continued to need ales. The need for Ales other than for cultural reasons, colonists' often preferred imported ales to local water supply, but in tropical places like India, local temperatures prevented successful brewing.

Some improvement came when Benjamin Wilson and Samuel Allsopp tried a new packaging technique designed to take advantage of the very shipping problems that were causing so many difficulties. They advised brewers to uncork freshly conditioned porters, allowing the beer to go flat, then re-cork the bottles and load them aboard departing ships. In theory, the natural rocking motion of the ship would help the beer achieve a second carbonation and "briskness" by the time it reached India. Two problems remained: The beers lacked shelf life, and beer drinking preferences tended to change in the tropics; the dark ales of London were possibly less satisfying to Britons in the heat of India. Why continue the effort to bring beer to India? Apparently, the high demand and low shipping rates could result in huge profit margins. But the lowshipping rates encouraged brewers to accept the risky gamble. Nevertheless, shipping costs still exceeded 20% of the beer cost.

Two factors greatly benefited Hodgson's brewing recipe invention. First, the Bow Brewery was the closest brewery to the headquarters of the East Indian men—the merchant ships that went back and forth between England and India. When the ships’ captains went looking for a brewery, they didn’t have to look far to find the Bow Brewery and George Hodgson. Second, the voyage had a fortunate affect on a particular batch of beer. George brewed up a batch of October-brewed stock bitter ale, which made it onto a ship headed for India. On the voyage to India—via the frequently turbulent waters off the Cape of Good Hope—Hodgson’s October stock ale underwent the sort of maturity in cask that would have taken up to two years in a cellar. The troops on Bengal loved pale ales, and local businesses could have sold more of it except for periodic and huge increases in the price of the imports. The market relied so heavily on Hodgson's deliveries that he could engage in a certain amount of price fixing. But he Hodgson reign wouldn't last long. Soon other brewers were matching color, quality, and flavor with Hodgson's India Ale. The Salt, Allsopp, and Bass breweries all claim to have been the first to copy Hodgson's style. Regardless of who was first, the successful recreation of Hodgson's recipe led to the ascendency of Burton-on-Trent as the brewing capital of England. The Salt, Allsopp, and Bass breweries all claim to have been the first to copy Hodgson's style. The secret to the Burton brewers' success came from the water, an ingredient often downplayed in beer recipe formulation. The sulfates of the Trent basin helped the Burton beers achieve their clarity and bitterness and allowed the Burton brewers to far exceed Hodgson's India Ale in clarity, hopping rate, and marketability. The export ales of Hodgson and the Burton brewers were truly export-only products until 1827, when a ship carrying cargo to India was wrecked in the Irish Sea. The cargo was auctioned, alerting locals to the existence of India Pale Ale. The pale ales became a success in Liverpool, and shortly afterward Londoners were clamoring for these export ales. A record of the original gravities of beers brewed in the Burton area suggests that by 1880-1900 most exports were of the India Pale Ale variety. Today’s IPA has little in common with Hodgson’s India Ale. IPA is pale ale made with higher hop content and higher alcohol content. Within the style IPA, there are huge variations. Some IPAs are stronger than others. Some are bitterer than others. Some have a floral note, some do not. The color of an IPA is either copper, pale blond, or golden. Examples of Modern IPA's

|

|---|